The Constitution has 27 amendments, the first ten making the Bill of Rights. The 1960s and 70s was the last period of time there was any significant action to amend the Constitution. Technically, the last amendment to be ratified was in 1992, due to a loophole in the amendment process.

Article V states the process of amending the Constitution. There are two methods for an amendment to be ratified (something Michael Rappaport focuses on in his commentary). The first, conventional method, is for at least 2/3 of both the House (290) and Senate (67) to vote on and propose an amendment. The amendment is then turned over to state legislatures to vote, now requiring 3/4 of the states (38) to ratify. Only then will the proposed amendment become an actual amendment to the Constitution.

The other, so far unused, method, takes the initiative from Congress, and gives it to the states, in this case, for 2/3 of the states legislatures to call for a special convention that would then propose an amendment, however at this point the convention would be independent even from state legislatures. The proposed amendment would then be referred to Congress who can either propose turning it over to state legislatures, or specially made state conventions in each state who must also pass the amendment by the 3/4 threshold. So, both ways entail a two-step process: the proposal stage that requires a 2/3 majority, and the ratification stage that requires 3/4. So far, the only method used is for Congress to propose an amendment, then ratified by state legislatures. Some legal scholars, like Akhil Reed Amar, believe there are other means for amending the Constitution besides what is explicitly mentioned in Article V, but for now we will concern ourselves with proposals in the article.

The first commentary by Jamal Greene, questions whether to create term limits for federal judges, as he says:

In a democracy, no one person should wield so much power for so long. Article III provides that federal judges “shall hold their offices during good behaviour.” [sic] In practice this language means they serve for life absent voluntary retirement or impeachment. Were we to draft the Constitution today, we would be wise to reconsider this provision.

His reasoning for this seems to rest on two main points: one, he argues in some cases judges simply become too old to effectively render judgements in cases, something which requires a person to be at the peak of their mental faculties. Two, he argues that life-term appointments makes the selection process of judges too political. Federal judges are nominated by the President, but approved by the U.S. Senate.

Greene argues that the example of other countries that have term limits or mandatory retirement ages might be a good example, and seems drawn to the idea of an 18-year term. 18 years is by mosts standards a long term in office, but many would still be opposed to limiting the terms of judges.

I think this is one of the most relevant and speaks to the need to limit the power of the court. It brings to light a massive contradiction in our supposedly democratic government (which as Wolin argues is more of a facade at this point) that we give so much power to an unelected body of people. Historically, the court has always been among the most conservative institutions of government, other than a relatively brief "liberal period" after World War II until the 1970s.

The second piece by Rachel Barkow, looks at the eight amendment of the Constitution and how it might relate to the current problem of imprisonment in the U.S. Despite the repeated claims to being the "land of the free," the U.S. leads the rest of the developed world in the number of people in prison, which as she points out is made up of significantly larger portions of minority groups in the country. Certainly, running prisons has become a profitable industry as of late, led by corporations like the Corrections Corporation of America (CCA) which also lobbies the government for longer prison terms and less leniency, not because it feels threatened by criminals, but because shorter prison terms would mean less business. However, private run prisons still make up only a small percentage of prisons in the US, most are maintained on public budgets.

The second piece by Rachel Barkow, looks at the eight amendment of the Constitution and how it might relate to the current problem of imprisonment in the U.S. Despite the repeated claims to being the "land of the free," the U.S. leads the rest of the developed world in the number of people in prison, which as she points out is made up of significantly larger portions of minority groups in the country. Certainly, running prisons has become a profitable industry as of late, led by corporations like the Corrections Corporation of America (CCA) which also lobbies the government for longer prison terms and less leniency, not because it feels threatened by criminals, but because shorter prison terms would mean less business. However, private run prisons still make up only a small percentage of prisons in the US, most are maintained on public budgets.

Barkow raises a point about the disproportionate number of minorities in the US who are incarcerated. This report, also from the Prison Policy initiative shows this to be the case as well. Black Americans make up only 13% of the population of the US, but almost 40% of people in prison. This demonstrates clearly the racist nature of our criminal justice system. However, I would also add there is an even stronger class dimension to this as well, as almost 100% of people in prison are poor. This includes both black and white. The same could be said about police killings as well, or any other number of pressing social issues in the US.

Some might say, "well that is because poor people commit more crimes." That might be true in some circumstances, but there also many documented instances of innocent people going to prison (even getting the death penalty) because they can not afford a decent legal defense, and of course many instances of guilty people getting off because they could afford high-priced defense attorneys or even avoiding charges altogether because of their social connections. Even when so-called "white collar" crimes occur these prisoners are usually kept apart from other prisoners and even in different institutions, like minimum security prisons, or what some call "Club Fed." Other non-economic crimes, or crimes of passion, I am not sure you can even say that poor people commit those crimes more often.

I made a similar point in my article but about the double standard in protests. However, I noticed a few people who commented on it focused on the racial aspects of it. I never said that the double standard was only a white/black issue, race plays a role but so does class, especially if you are anti-capitalist. None of the people who showed up on Jan. 6 were anti-capitalist, and most of them were middle class if not wealthy.

This goes back again to a dialectical approach to understanding these things. Dialectics looks at the connections between different things, in this case race and class. To focus on one or the other leads to an overly simple explanation. Instead, look to the connections between race and class, including the historical aspects of this over time, and you get a better picture of what is going on.

A dialectical approach helps you understand the complex nature of society as a whole instead of seeing things in isolation. Even the obsession some people have with law and order and crime suggests a kind of tunnel vision on their part. People who are concerned about "street crime" do not seem that troubled by Wall St. banks sucking all the resources out of society, profiting off debt and other non-productive activities, or that 70,000 people a year die in this country because of lack of healthcare. Dialectics gives you a larger view of society by looking at the various parts of society that make up the whole.

Anyway, Barkow looks to the Eighth Amendment to the Constitution, or what we refer to as the Bill of Rights (the first ten amendments) which bans the use of "cruel and unusual punishment." She argues that the prohibition against cruel and unusual punishment should prohibit excessively long prison sentences as well:

Anyway, Barkow looks to the Eighth Amendment to the Constitution, or what we refer to as the Bill of Rights (the first ten amendments) which bans the use of "cruel and unusual punishment." She argues that the prohibition against cruel and unusual punishment should prohibit excessively long prison sentences as well:

As I have suggested elsewhere, clarifying and expanding the Eighth Amendment could help. It should specifically state that excessive terms of incarceration are prohibited, just as it bans excessive fines. It should expressly prohibit mandatory sentences so that every case gets the benefit of individualized attention by a judge. And it should insist that legislatures create a record showing that they considered empirical evidence about the law's likely impact. It is important to see that before any action can be undertaken, there must be some groundwork for this action in the Constitution. In this case she argues that the Eighth Amendment lays the groundwork that would make the movement towards shorter prison terms a legitimate, and legal course of action.

The third piece by Akhil Reed Amar, looks at the limitations on naturalized citizens for holding office, specifically the President. The Constitution states that only citizens born in the U.S. are eligible to be President of the U.S., as he says:

But those American citizens who happen to have been born abroad to non-American parents — and who later choose to become “naturalized” American citizens — are not the full legal equals of those of us born in the U.S. True, naturalized Americans have always been allowed to serve as cabinet secretaries, Supreme Court justices, senators and governors. And at the founding, anyone already a citizen could be president, regardless of birthplace. (Alexander Hamilton, for example, though born in the West Indies, was fully eligible to serve as president under the Constitution he himself helped draft.) But modern-day naturalized citizens are barred from the presidency simply because they were born in the wrong place to the wrong parents. We can look back to the readings from Bourne and Chesterton and relate their views on transnationalism or as Chesterton called it the "the nationalization of the internationalized" to this restriction. Do you think Bourne and Chesterton would be in favor of lifting this restriction? Do you think it is fair to continue this restriction, or should any citizen regardless of birth be eligible to one-day become President of the U.S.

The fourth piece by Elizabeth Price Foley argues for the importance of federalism. Federalism is a doctrine which divides the power of government between the federal government and states that retain some independence and autonomy. Some other countries have what is called a unitary government where the top-level of government appoints all the lower levels as well, thus power and control is in the hands of the top government officials. In our country, the governor of New York for example has certain freedoms to act that the President and Congress cannot limit. In practice, however, especially in recent times the extent and influence of the federal government has increased, mainly as a result of the influence the federal government has in directing funds for the states in multiple areas like education or even to maintain roads.

Foley argues that this expansion of government power threatens the idea of federalism which the Constitution is based on:

Federalism isn't about states' rights. It's about individual liberty. The Supreme Court emphasized this in Bond v. United States (2011): "By denying any one government complete jurisdiction over all the concerns of public life, federalism protects the liberty of the individual from arbitrary power. When government acts in excess of its lawful powers, that liberty is at stake." And lest you think this emanates from the court's right wing, Bond was unanimous.

As the last line indicates however, this view has increasingly become seen as more of a conservative or right-wing opinion. She goes on to point out how the Supreme Court had recently ruled against certain aspects of the health care law that would force state governments to act.

The fifth piece by Alexander Keyssar argues to abolish the electoral college. We know the President is not elected through a direct popular vote, but is chosen by electors equal to each states representation in Congress, meaning that elections are decided on a state by state basis. This is one of the more well known and controversial aspects of the Constitution today. As he says:

Moreover, we have learned a lot in the last 225 years about shortcomings in the framers’ design: the person who wins the most votes doesn’t necessarily become president; the adoption of “winner take all” rules (permitted but not mandated by the Constitution) produces election campaigns that ignore most of the country and contribute to low turnout; the legislature of any state can decide to choose electors by itself and decline to hold an election at all; and the complex procedure for dealing with an election in which no candidate wins a clear majority of the electoral vote is fraught with peril. As a nation, we have come to embrace “one person, one vote” as a fundamental democratic principle, yet the allocation of electoral votes to the states violates that principle. It is hardly an accident that no other country in the world has imitated our Electoral College.

The third piece by Akhil Reed Amar, looks at the limitations on naturalized citizens for holding office, specifically the President. The Constitution states that only citizens born in the U.S. are eligible to be President of the U.S., as he says:

But those American citizens who happen to have been born abroad to non-American parents — and who later choose to become “naturalized” American citizens — are not the full legal equals of those of us born in the U.S. True, naturalized Americans have always been allowed to serve as cabinet secretaries, Supreme Court justices, senators and governors. And at the founding, anyone already a citizen could be president, regardless of birthplace. (Alexander Hamilton, for example, though born in the West Indies, was fully eligible to serve as president under the Constitution he himself helped draft.) But modern-day naturalized citizens are barred from the presidency simply because they were born in the wrong place to the wrong parents. We can look back to the readings from Bourne and Chesterton and relate their views on transnationalism or as Chesterton called it the "the nationalization of the internationalized" to this restriction. Do you think Bourne and Chesterton would be in favor of lifting this restriction? Do you think it is fair to continue this restriction, or should any citizen regardless of birth be eligible to one-day become President of the U.S.

The fourth piece by Elizabeth Price Foley argues for the importance of federalism. Federalism is a doctrine which divides the power of government between the federal government and states that retain some independence and autonomy. Some other countries have what is called a unitary government where the top-level of government appoints all the lower levels as well, thus power and control is in the hands of the top government officials. In our country, the governor of New York for example has certain freedoms to act that the President and Congress cannot limit. In practice, however, especially in recent times the extent and influence of the federal government has increased, mainly as a result of the influence the federal government has in directing funds for the states in multiple areas like education or even to maintain roads.

Foley argues that this expansion of government power threatens the idea of federalism which the Constitution is based on:

Federalism isn't about states' rights. It's about individual liberty. The Supreme Court emphasized this in Bond v. United States (2011): "By denying any one government complete jurisdiction over all the concerns of public life, federalism protects the liberty of the individual from arbitrary power. When government acts in excess of its lawful powers, that liberty is at stake." And lest you think this emanates from the court's right wing, Bond was unanimous.

As the last line indicates however, this view has increasingly become seen as more of a conservative or right-wing opinion. She goes on to point out how the Supreme Court had recently ruled against certain aspects of the health care law that would force state governments to act.

The fifth piece by Alexander Keyssar argues to abolish the electoral college. We know the President is not elected through a direct popular vote, but is chosen by electors equal to each states representation in Congress, meaning that elections are decided on a state by state basis. This is one of the more well known and controversial aspects of the Constitution today. As he says:

Moreover, we have learned a lot in the last 225 years about shortcomings in the framers’ design: the person who wins the most votes doesn’t necessarily become president; the adoption of “winner take all” rules (permitted but not mandated by the Constitution) produces election campaigns that ignore most of the country and contribute to low turnout; the legislature of any state can decide to choose electors by itself and decline to hold an election at all; and the complex procedure for dealing with an election in which no candidate wins a clear majority of the electoral vote is fraught with peril. As a nation, we have come to embrace “one person, one vote” as a fundamental democratic principle, yet the allocation of electoral votes to the states violates that principle. It is hardly an accident that no other country in the world has imitated our Electoral College.

The sixth piece by Michael Rappaport looks at the process by which the Constitution is changed. Paradoxically he argues that the process of changing the Constitution has come to a point where it is virtually impossible to change. There are two methods for changing the Constitution. The first requires that 2/3 of both houses of Congress agree to an amendment which is then sent to the states to ratify, or approve of the proposed amendment. There is a second method but is has never been used as he says:

The second method is for two-thirds of the state legislatures to call for a constitutional convention that would then propose an amendment (which, again, would have to be ratified by the states). This second method has never been used, because the state legislatures fear a runaway convention. They are concerned that if they call a convention to draft a balanced budget amendment, the convention will end up proposing an amendment on same-sex marriage or school prayer. This argument matches up well with Foley's federalist argument since it reserves a more active role for the states, again quoting his argument:

The Constitution should be changed to eliminate the possibility of a runaway convention. The best way to do this is to dispense with a constitutional convention and instead have the state legislatures agree to propose a specific amendment. But any method that allows for a working alternative to Congress’s amendment monopoly would be an enormous improvement.

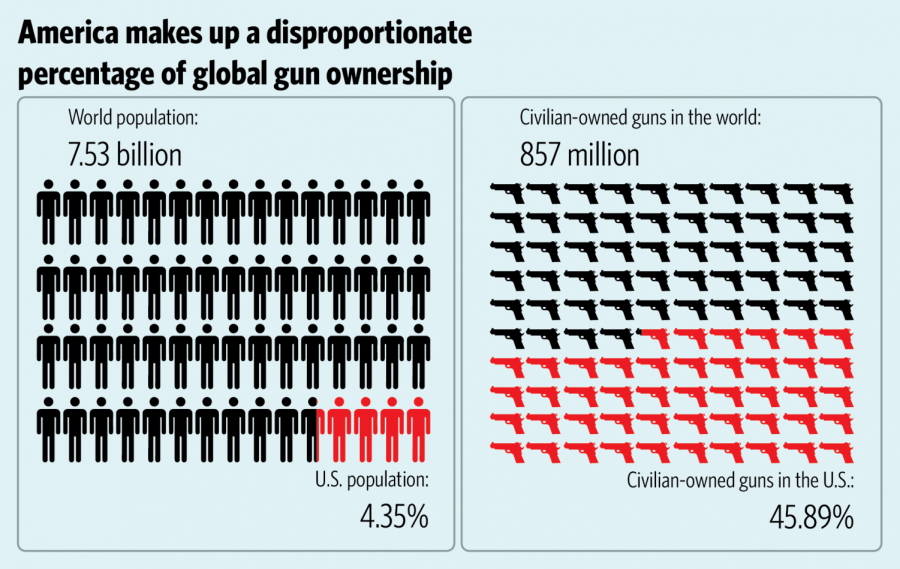

The seventh piece by Melynda Price deals with another highly publicized and controversial aspect of the Constitution, the "right to bear arms" in the second amendment. Price who is in favor of abolishing this right argues:

I am not naïve enough to believe that doing away with the Second Amendment would do away with gun violence, but I know firsthand the impact of guns and gun shots on children. This nation was constructed and reconstructed in the aftermath of violent and bloody conflicts. Still, the Framers believed that not only the Constitution, but also the peaceful way the document was created, would penetrate the Americans' minds and change they engaged. The Constitution would be the only weapon needed unless there was an external enemy. Arguably, the issues of guns and the right to bear arms is one of the most controversial issues now. Even if you do believe firearms should be regulated, how would you regulate it?

The eight piece by Jenny Martinez deals with the interpretation of the Constitution in a more international setting, that being how important are treaties signed with other countries in the legal process of this country. Martinez points to what is called the "supremacy clause" in the Constitution, “Constitution, and the Laws of the United States which shall be made in pursuance thereof; and all treaties made, or which shall be made, under the authority of the United States, shall be the supreme law of the land; and the judges in every state shall be bound thereby, anything in the constitution or laws of any state to the contrary notwithstanding.”

However she addresses the often conflicting tendency of courts to ignore treaties that have been signed with other countries, as she points out:

But the Supreme Court has interpreted the supremacy clause in ways that contradict its text and original purpose; the court has suggested that the clause doesn’t mean what it says as far as treaties are concerned. One of the strangest of these decisions came a few years ago in a case involving Texas’s failure to notify Mexican citizens facing the death penalty that they were entitled by a treaty to speak to their consulate. In that case, Medellín v. Texas, the Supreme Court held that the treaty (and a decision of the International Court of Justice interpreting it) weren’t actually enforceable against Texas. The ninth piece is by Randy Barnett and concerns the Commerce clause of the the Constitution. This gives Congress the power to regulate business in the country. Barnett argues that this power also has grown too much and exceeds what it is meant for. He argues the clause should be reworded as:

"The power of Congress to make all laws that are necessary and proper to regulate commerce among the several states, or with foreign nations, shall not be construed to include the power to regulate or prohibit any activity that is confined within a single state regardless of its effects outside the state, whether it employs instrumentalities therefrom, or whether its regulation or prohibition is part of a comprehensive regulatory scheme; but Congress shall have power to regulate harmful emissions between one state and another, and to define and provide for punishment of offenses constituting acts of war or violent insurrection against the United States." Compared with its original text in the Constitution which is much shorter (Article 1 Section 8 Clause 3): "to regulate commerce with foreign nations, and among the several states, and with the Indian tribes." Is this more complex version necessary? Barnett argues that this is more in line with the original intention, but he does not make an argument for why the original intention is better. In other words why is it better to return to the original meaning of the commerce clause, given that the environment is much more complex now and boundaries between states much less important?

The final piece by Pauline Maier looks at the most well known part of the Constitution, the first amendment to the Bill of Rights. However she argues that the wording of the text is flawed and argues it should be expanded on:

“Congress shall make no law” is a peculiarly stingy way to begin an amendment that protects the rights of conscience, speech, press, assembly and petition. James Madison proposed more capacious language for those rights. He would have said, for example, that “the civil rights of none shall be abridged on account of religious belief or worship, nor shall any national religion be established, nor shall the full and equal rights of conscience be in any manner, or on any pretext infringed.” He would also have stated that “the people shall not be deprived of their right to speak, to write, or to publish their sentiments; and the freedom of the press, as one of the great bulwarks of liberty, shall be inviolable.” She argues that this would clearly separate the protections giving to people and to corporations which also appeal to first amendment rights to justify lobbying the government.

These authors represent different political perspectives and isolate different problematic areas of the Constitutions which continue to be debated in the present. Some call for new interpretations of how we understand our rights, others for re-wording or altering certain parts of the text, others still call for getting rid of what they see as outdated features of the Constitution.

People often say that the Constitution is a "living document" meaning that it changes and adapts itself to fit the needs of the era. These writers and others suggest several ways in which the Constitution can be adapted. What areas of the Constitution would you try improve on? That would definitely be a question people should be asking themselves after reading this, would you choose something else? Do you find one of the writers more persuasive than others? What is offered here is of course only a little preview, but if you like any of these authors you should try reading up on them more.

I am not naïve enough to believe that doing away with the Second Amendment would do away with gun violence, but I know firsthand the impact of guns and gun shots on children. This nation was constructed and reconstructed in the aftermath of violent and bloody conflicts. Still, the Framers believed that not only the Constitution, but also the peaceful way the document was created, would penetrate the Americans' minds and change they engaged. The Constitution would be the only weapon needed unless there was an external enemy. Arguably, the issues of guns and the right to bear arms is one of the most controversial issues now. Even if you do believe firearms should be regulated, how would you regulate it?

The eight piece by Jenny Martinez deals with the interpretation of the Constitution in a more international setting, that being how important are treaties signed with other countries in the legal process of this country. Martinez points to what is called the "supremacy clause" in the Constitution, “Constitution, and the Laws of the United States which shall be made in pursuance thereof; and all treaties made, or which shall be made, under the authority of the United States, shall be the supreme law of the land; and the judges in every state shall be bound thereby, anything in the constitution or laws of any state to the contrary notwithstanding.”

However she addresses the often conflicting tendency of courts to ignore treaties that have been signed with other countries, as she points out:

But the Supreme Court has interpreted the supremacy clause in ways that contradict its text and original purpose; the court has suggested that the clause doesn’t mean what it says as far as treaties are concerned. One of the strangest of these decisions came a few years ago in a case involving Texas’s failure to notify Mexican citizens facing the death penalty that they were entitled by a treaty to speak to their consulate. In that case, Medellín v. Texas, the Supreme Court held that the treaty (and a decision of the International Court of Justice interpreting it) weren’t actually enforceable against Texas. The ninth piece is by Randy Barnett and concerns the Commerce clause of the the Constitution. This gives Congress the power to regulate business in the country. Barnett argues that this power also has grown too much and exceeds what it is meant for. He argues the clause should be reworded as:

"The power of Congress to make all laws that are necessary and proper to regulate commerce among the several states, or with foreign nations, shall not be construed to include the power to regulate or prohibit any activity that is confined within a single state regardless of its effects outside the state, whether it employs instrumentalities therefrom, or whether its regulation or prohibition is part of a comprehensive regulatory scheme; but Congress shall have power to regulate harmful emissions between one state and another, and to define and provide for punishment of offenses constituting acts of war or violent insurrection against the United States." Compared with its original text in the Constitution which is much shorter (Article 1 Section 8 Clause 3): "to regulate commerce with foreign nations, and among the several states, and with the Indian tribes." Is this more complex version necessary? Barnett argues that this is more in line with the original intention, but he does not make an argument for why the original intention is better. In other words why is it better to return to the original meaning of the commerce clause, given that the environment is much more complex now and boundaries between states much less important?

The final piece by Pauline Maier looks at the most well known part of the Constitution, the first amendment to the Bill of Rights. However she argues that the wording of the text is flawed and argues it should be expanded on:

“Congress shall make no law” is a peculiarly stingy way to begin an amendment that protects the rights of conscience, speech, press, assembly and petition. James Madison proposed more capacious language for those rights. He would have said, for example, that “the civil rights of none shall be abridged on account of religious belief or worship, nor shall any national religion be established, nor shall the full and equal rights of conscience be in any manner, or on any pretext infringed.” He would also have stated that “the people shall not be deprived of their right to speak, to write, or to publish their sentiments; and the freedom of the press, as one of the great bulwarks of liberty, shall be inviolable.” She argues that this would clearly separate the protections giving to people and to corporations which also appeal to first amendment rights to justify lobbying the government.

These authors represent different political perspectives and isolate different problematic areas of the Constitutions which continue to be debated in the present. Some call for new interpretations of how we understand our rights, others for re-wording or altering certain parts of the text, others still call for getting rid of what they see as outdated features of the Constitution.

People often say that the Constitution is a "living document" meaning that it changes and adapts itself to fit the needs of the era. These writers and others suggest several ways in which the Constitution can be adapted. What areas of the Constitution would you try improve on? That would definitely be a question people should be asking themselves after reading this, would you choose something else? Do you find one of the writers more persuasive than others? What is offered here is of course only a little preview, but if you like any of these authors you should try reading up on them more.

Finally, I would like to add what I think is missing from this. It is interesting that not one of these writers thought to include things like a right to healthcare, housing, education, or other basic means of life. We will talk about this more when we talk about the different kinds of rights later in the class. In short, most other countries besides the US do recognize these as important social rights.

However, Franklin Roosevelt did speak of these as important rights, what he called an "Economic Bill of Rights" or even a Second Bill of Rights. Here is a link to him speaking about this in 1944.

Here is the text of the speech which is slightly different.

He concludes by saying:

All of these rights spell security. And after this war is won we must be prepared to move forward, in the implementation of these rights, to new goals of human happiness and well-being.

America's own rightful place in the world depends in large part upon how fully these and similar rights have been carried into practice for our citizens.

In a similar fashion, Karl Marx once wrote: "The realm of freedom begins when the realm of necessity is left behind." In other words, you really are not free when you have to worry about securing the basic necessities of life, especially when this makes you dependent on others to secure these means (i.e. an employer). For all of the talk about our cherished freedoms in this country, if we adopt this definition then most people are not free. Some are, but just the top 10% or even 1%. This has always been an argument made by socialists, even before Marx, and I think it it is still one of the strongest arguments you can make, and really exposes the contradictions at the heart of our society: that we are not really free in spite of constantly being told that we are, which at least shows you that freedom is one of the most important things people can strive for.

Marxian economists like Richard Wolff still make this argument today, in fact many do, but he seems to really emphasize this issue. How can you say you are free when you spend most of the hours of a day (at least 8 hours) for most of your life (30-40 years of your adult life) in the workplace which is basically run like a dictatorship?

The fact that things like healthcare are tied to your employment reduces freedom and makes you more dependent on your employer. Former Chair of the Federal Reserve, Alan Greenspan referred to this and the fact that workers are not asking for higher wages as the "traumatized worker" syndrome. He never used this phrase in public, but in private according to reporter Bob Woodward. He did publicly speak of "greater worker insecurity." Here is a link to an article about this:

This has implications in foreign policy as well. We are constantly being told that America is spreading freedom around the world, but that is a lie and one easily shown by the record of supporting dictatorships, or the pointless devastation we have brought to countries like Vietnam, Afghanistan and Iraq. Now, as we are gearing up for another Cold War against China we are told that this is about "freedom v. authoritarianism," but it is really about preserving the capitalist American empire in the face of its greatest challenge since the Soviet Union, as well as justifying America's massive military expenditures, and finding a scapegoat to blame all the problems of America on, especially the persistence of poverty and the reduction of living standards for middle class Americans, which we are told is because China is "stealing American jobs" and things like that.

I have enjoyed reading the discussion posts so far. I am looking forward to hearing what people have to say about this and what these authors have said about the Constitution.

.jpeg)